New week, new start, big plans, can’t be as bad as last week, but first, let’s log on and find out what’s going on in the world. Friend’s Facebook video, man hurting a dog in an elevator. Comment, like, share; love animals, hate cruelty. Some idiot replies, ‘we’re in a pandemic, animals don’t matter’. Put him in his place. Bit of a row when the other half puts our cat outside. Get some cat treats later.

Need to chill now, listen to a few video tunes, then get started. Ad comes on – drinking probiotics is like being in an ancient, mystical Japanese pagoda. Scroll down news feed: takeaway coffee ‘classed as’ picnic by covid police; Pfizer vaccine turns you into a chimpanzee; big mad baby Trump wanted nuclear war; Percy Pig in red tape Brexit tax shock.

Wears you out, just looking at it all. And, inexplicably, makes you hungry all of a sudden. Luckily, there’s still time to get to McDonald’s before they stop serving breakfast. Goodbye home-made vegetable soup. One more day in front of the TV won’t hurt. The new life can start tomorrow.

Often it seems like, however much we dream for something better, real life will soon kick in and drag our heads unceremoniously out of the clouds. Except, more often than not, it’s not life that does this to us, it’s fake news. Or, to be precise, the processes that deliver fake news to us, the way we interact with the news and the effect it all has on us.

We’ve all heard the made-up stories about politicians, celebrities, 5G and Covid-19, but that’s only one element of the fake news bombardment, which we are increasingly subjected to every time we go online.

Even the term ‘fake news’ is fake, as by focusing on the content (i.e. the ‘news’) it hides in plain sight, the fakery inherent in the faker’s communication process. Subsequent discussion is then focused solely on a piece of content, with which we, or society, either agree or disagree.

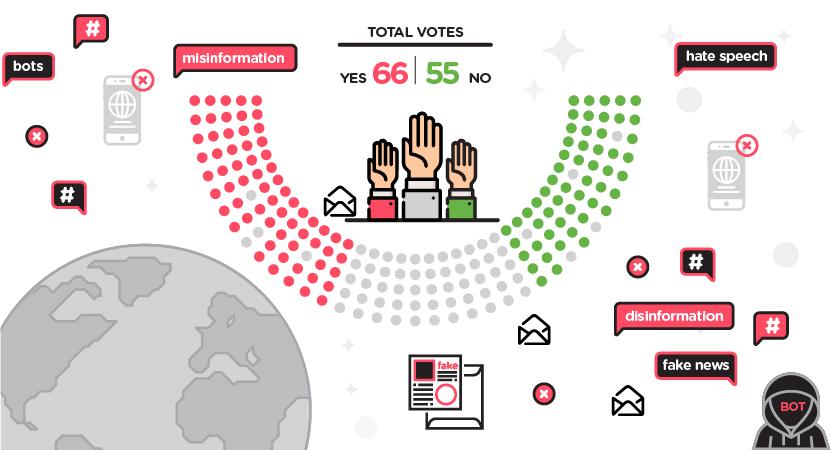

Manipulative disinformation would more accurately describe that which we’re exposed to, online, on a daily basis. An EU Commission’s report on fake news and online disinformation, out last March, referred to a need to deal with “all forms of false, inaccurate or misleading information designed, presented and promoted to intentionally cause public harm or for profit”.

Fakers have lots of subtle tricks to get their messages past our radar and into our minds. As the introductory scenario shows, they might try and hide the source of their content and present old content as current. Imagery triggers positive associations, the passive-tense hides their own motivation, perspective and the process of cause and effect. They’ll make biased comment and exaggerate claims while preaching objectivity. They’ll present opinion as fact and deliberately select and omit content, for effect.

Fakers might be anti-vaxxers, political spin doctors, marketing consultants or just deluded fantasists with a laptop; but they all want the same thing, that their intervention in our lives should evoke a desired response. Stir up emotions, trigger cravings to eat, smoke, drink, use, buy, vote, join, post.

Using these deceptions, the fakers can misdirect, influence, and foster dependence. And like lemmings to a cliff’s edge, we follow them, blissfully unaware of what’s going on.

Edward Bernays (1891-1995) isn’t a household name, which is apt considering the nature of his immense, but almost wholly hidden, influence on the modern world.

Bernays was Freud’s nephew and during the early to middle decades of the 20th century, he applied his uncle’s insights into the human psyche to the world of publicity, marketing, propaganda and social engineering. Bernays wrote best-selling books, worked for governments and corporations, and bequeathed the world many of the dark arts used by today’s online manipulators.

Bernays believed that the masses were driven by factors outside their understanding, which left them open to manipulation by the capable few. “If we understand the mechanism and motives of the group mind, it is now possible to control and regiment the masses according to our will without them knowing it,” Bernays wrote in ‘Propaganda’ in 1928.

He convinced the world that budget fast-food chicken was "finger-lickin' good", that bacon and eggs was a healthy breakfast and that if you drank Dos Equis beer you would be just like the ‘Most Interesting Man in the World’, who featured in the ads. Most famously, Bernays’s ‘torches of freedom’ campaign convinced millions of women to start smoking cigarettes as a sign of emancipation and independence.

When it’s all put like that, we can see this sort of thing for what it is. The problem is that the manipulators tend to put their disinformation across in such a way that we don’t see it at all.

Opinion is divided as to why we fall for it. Some believe we think what we want to think when we encounter new content, rather than attempting to discover the truth about the content. Others say we don’t exercise critical thinking skills, relying on instinctive response to the information encountered, particularly when glancing over content, or just the headline.

Add to that what behavioural economics founder George Lowenstein said about our natural curiosity to resolve information gaps – particularly when faced with a question or puzzle that has an unknown or unexpected answer.

Then apply Richard Brodie’s concept of the meme to understand what these information gaps are filled with. Brodie, the original author of Microsoft Word, wrote that everyone has a collection of beliefs, attitudes and sponsoring thoughts (memes) passed on by our families, culture and society. These memes influence how we see things and what we do, often without us realising it, and we pass them on to those around us.

With all that in mind, think about looking at content, on your phone, while eating a sandwich, texting a friend and listening to some music.

Tristan Harris, former Google design ethicist and star of the recent Netflix film ‘Social Dilemma’, which warns of the dangers of the internet and social media, is of the view that digital technology is used to exploit the biases, vulnerabilities and limitations inherent in human nature. It can do this, he says, because digital technology has evolved faster than the human brain, which remains much as it was when we were hunter gatherers.

Harris explains that our emotional need for social validation, approval and correctness can create addiction to ‘likes’ and ‘ticks’. For the rest of the time when we’re not getting noticed online, we suffer quasi-withdrawal symptoms.

It’s what cognitive behaviouralists call random reinforcement. Addiction is fed by intermittent reward, with the behaviour desired by the manipulator much more likely to persist than if reward is given every time or never given. It’s the same reason gambling is so addictive.

The basic social media business model, surveillance-based advertising, capitalises on this. On social media platforms, algorithms track users’ behaviour in order to sell targeted ads, but also to influence and change users’ behaviour so we spend more time scrolling, liking, buying, believing. The idea is to trigger emotions, and negative emotions are the easiest to trigger.

It’s why we’re drawn to attention-grabbing sensationalist content. We want to vent our anger, indignation, outrage and frustration and negate our sadness, guilt, shame and fear. Our reward for sharing, liking or commenting on such content is, according to a June 2021 Cambridge University study, around twice as much engagement and hence validation.

Add to that, Harris says, our tendency to gather in likeminded groups and accede to social pressure and it’s easy to see why the provocative, negative content favoured by online manipulators tends to propagate faster and wider.

The obvious answer to all this is to come off social media and not use the internet unless you want to message friends, buy a pizza or check the football scores. Most people can’t or won’t do that, particularly during a lockdown pandemic. But there are actions that can be taken to help us handle manipulative disinformation.

For a start, we can turn off notifications, uninstall apps and change privacy settings or make a conscious choice not to view posts and videos suggested by the algorithms.

We can also become more switched on about the use of manipulative language. George Orwell’s ‘Politics and the English Language’ presents words, phrases, metaphors used to influence, confuse, imply and deceive. Read anything by Bernays and you’ll see how manipulative disinformation is done, straight from the horse’s mouth, mixed-metaphor cliché intended.

In 2020, MIT researchers set up a project that uses virtual-reality technology to help people recognise digitally manipulated video. They used a faked video of Richard Nixon talking about the Moon landings, with a voice actor, synthetic speech technology and video dialogue replacement techniques to replicate the movement of Nixon’s mouth. This makes it look like a speech that Nixon never delivered publically, was actually made in front of a TV camera. The MIT team have set up an educational website and a course, based around this video, to help people understand how fake images are made and used to spread disinformation.

“Media literacy helps [people] cultivate their inner critic, transforming them from passive consumers of media into a discerning public,” says Dr Joshua Glick from MIT’s Open Documentary Lab, who is involved in the project.

Dr Martin Moore, an expert in political communication education from King’s College London, agrees about the importance of digital media literacy but adds that interventions like this are “long-term policy aims and not an answer to our current predicament, or even something that will have an impact in the next year or so”.

He continues: “There are technical changes that can be made that would have knock-on effects down the line.”

At the Stevens Institute of Technology, researchers use machine learning to uncover the hidden connections that underlie fake news and social media misinformation.

The researchers used natural-language-processing technology to analyse news from larger open-sourced data sets, such as FakeNewsNet, Twitter and Celebrity, and found that phrasings and word patterns differ in fake news: less sophisticated vocabulary that is high on imagery and provocative, negative language. An algorithm containing knowledge graphs helps identify the relationships between entities in a fake news story as false.

There are more technologies – watermarking and digital signatures, tech that can help explain how information travels around the internet, browser extensions with fact-checking or quality ranking services. Is the average person tech-savvy enough to access them? Should we have to, when the issue has been created by the social media platforms and is being capitalised on by organisations and individuals that use them?

A University of Kansas study, published in March 2021, found that flagged information was more likely to be scrutinised by users and that, without notification, people found it harder to identify and disregard fake news.

In the UK, under the Johnson government‘s online safety bill expected to become law later this year or next, social media platforms will be fined up to 10 per cent of their global turnover if they fail to take down content that the government considers harmful to the public. The EU Commission’s fake news report recommends that big tech companies and public authorities share data to enable independent assessment of their efforts to combat disinformation.

Many would like modifications made to the way in which social media platforms work. This June, a coalition of consumer protection and digital rights organisations and experts in Europe and the US called for governments and social media platforms to take action against commercial surveillance.

The report proposed alternative digital advertising models, for instance where advertisers have more control over where ads are shown, or where consumers have opted to see certain adverts. Harris would like to see heavy taxes levied on the practice of monetarising attention and new subscription services that enable and empower our offline lives. Jonathan Haidt, a social psychologist at New York University Stern School of Business suggests obscuring ‘like’ and ‘share’ counts to enable content to be evaluated on its own merit.

Haidt also wants major platforms to insist on identity verification for user accounts and programme AI technology to recognise and challenge users when they post potentially hurtful messages.

Dr Moore suggests that platforms should require a user’s permission before someone adds them to a group and impose more constraints on where users can send content. Most importantly he’d like to see more source identification.

“You could click on a button to see the details of that post,” Moore says. “You’d only need a small proportion of users to make clear what the providence is, and you’d have a healthy and constructive ecosystem.”

Right now, though, there’s still too much rubbish getting through. You only have to go online for ten minutes to realise that.

The problem is that the manipulators are achieving precisely what they want and will continue to do so while things stay as they are. Platform owners are raking in the dollars, advertisers are selling, spin doctors, extremists and conspiracy theorists are influencing.

And it’s not just the obvious scammers who are it. While researching this article, I was reading an online article in a national newspaper which was criticising disinformation. Suddenly, halfway down the page an advert appeared. Incredibly, it asked me if I’d like to sign up for a social media marketing course.

Edward Bernays would be proud of his successors.

Tech to fight back

• Bad News: a game that exposes players to fake news tactics in its role as a fake news baron. To win, publish headlines that attract the most followers.

• Bot Sentinel: tracks Twitter for unreliable information and accounts.

• Exiftool: provides metadata information about a piece of content’s source, timestamp, creation, and whether modifications have been made.

• Misinformation Detector: web-based decentralised trust protocol that tracks news credibility, by analysing what content is linked to and how it is spread (in development).

• Twitter Trails : algorithm analyses spread of a story and how users react.

• Logically: picks out and verifies key claims within a piece of content, picks out positive, negative and neutral takes on each story.

• Factmata: contextual understanding algorithms that can identify threatening, growing narratives.

• Storyzy: detects and classifies fake news sources and analyses URLs and rank news sources.