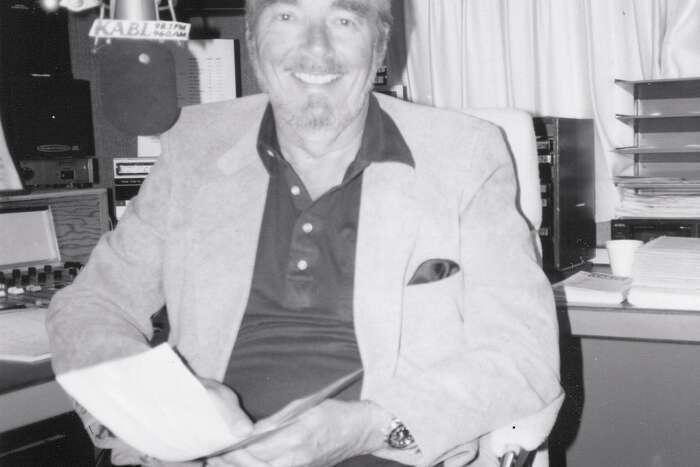

Gosney, who made his living as a book, periodical and multimedia publisher, had a rare combination of traits that surfaced as both a personal computer nerd and a charismatic party planner. His longest running event was the Goz Salon, a think tank and speakers bureau held in the living room of his home near Ocean Beach in the Outer Richmond.

Gosney died April 28 at home, three months after being diagnosed with bile duct cancer, said his daughter, Kate Gosney-Hoffman. He was 67, and had made the decision to stop all medical interventions including painkillers and sedatives. His last moments were spent with his daughter holding his hand and his year-old granddaughter, Clara, holding his gaze.

More for you“She smiled and gently carried him over,” said Gosney-Hoffman said. “He orchestrated his death as he did just about everything else. He was the master at it.”

As an orchestrator, Gosney was late to the Gathering of the Tribes that sparked the Summer of Love. But his timing was perfect for the next generation of counterculture seekers who came to San Francisco in the 1990s. As a matchmaker, he introduced the city’s tech pioneers to the likes of Ken Kesey, Ram Dass, Timothy Leary, Wavy Gravy, Todd Rundgren and both Browns — Jerry and Willie.

“Michael was the most connected person I have ever met and he had a superhuman ability to put people together in ways that inspired profound friendships and vital creative endeavors,” said Steve Wagner, former host of “Film Trip” on KGO-TV and director of the San Francisco Art Exchange, a dealer in original rock photography and album cover art.

“He really brought together the spirit of the 1960s counterculture with the 90s cyber culture, the early adopters of the internet,” said Don Lattin, author of “Changing Our Minds: Psychedelic Sacraments and the New Psychotherapy.” “He missed the glory days himself, so he really kept that spirit alive.”

Gosney launched Verbum, a magazine of computer art, in 1986. It is credited as being one of the first magazines to be printed solely with desktop publishing tools. In essence, software replaced the art director and the printer physically laying out the pages. He folded the print edition in 1991 and took his magazine online as Verbum Interactive, one of the first platforms for digital art, much of which Gosney created himself.

“Michael did the first of so many things that were seminal,” said software designer Alden Bevington, noting the San Francisco Bay Area Deep Green Conference, held in 2011 and 2012. It featured panels on ecology and cannabis legislation and exhibitions of green cultivation techniques. “He came from the philosopher-class of the early internet, which is actually a dying breed.”

Michael William Gosney was born July 11, 1954 in Pittsburgh. His dad, William was a sales manager for a plastics company. His mom, Lou worked in real estate and raised three kids, Michael being the oldest. At Shawnee Mission South High School he played tight end on the football team and center on the basketball team while also writing poetry. After graduating in 1972 he went to Arizona State University before transferring to the University of Kansas.

But he got bored with school and never graduated. In the mid-1970s he drifted to San Diego to meet up with some friends, and was working as a bellhop at the Town and Country Resort when he met Jeanette Menter, a clerk at the front desk. They were married in 1978 and had two daughters, Kate and Rachel. They divorced in 1990 and Gosney never remarried.

Gosney was foremost a man of letters, and his first startup was a San Diego literary agency called the Word Shop. From there he opened his own publishing house, Avant Books. His titles ranged from a biography of John Muir to the first English translation of the Greek play “Buddha,” by Nikos Kazantzakis.

He came up with the idea for the Digital Be-In while still living in San Diego, in 1988.

“Michael recognized that San Francisco was ground-zero for the digital revolution,” said Wagner, “and he needed to be where the action was.”

He introduced himself at his first Be-In, a private party put on by Verbum Interactive. It piggybacked on Macworld Expo, a trade show at Moscone Center for devotees of Apple computers.

“The Mac was born of that whole ‘60s scene,” said Gosney at the time. “It’s all about spiritual power, personal power and evolution. Now, all throughout the computer business, you find people who were active in the ‘60s in San Francisco.”

Within five years the Digital Be-In was big enough to invite the general public as a ticketed event that combined music and dance with a showcase of new technology and a very primitive attempt at live streaming.

“The ‘60s reached its arms out to the ‘90s, and the ‘90s wired back,” wrote San Francisco Examiner reporter Scott Rosenberg, who covered the 1992 anniversary event. “At one end of the club, booths sold Oracle facsimile editions and T-shirts displaying ‘Peace’ in 37 languages (100% cotton, preshrunk). At the other, a sign read, “Welcome to the digital realm,” and a narrow hallway led to a cybernetic playroom.”

Gosney co-produced versions of the Digital Be-In in Tokyo and London. His final San Francisco Digital Be-In was on Jan. 12, 2017, the 50th anniversary of the Human Be-In.

“After that, he retired the concept,” said Wagner. “He was onto other things.”

One month ago, Wagner spent two weeks with Gosney to help organize his archive of artworks, essays and a massive number of digital files. Gosney’s goal was to donate the archive to either UC Berkeley or Stanford University. But his illness overtook him before he could make the necessary introductions. His colleagues and disciples plan to finish the project, however long it takes, and place Gosley’s material and digital works with an academic institution.

“The archive is intended to mark the transition from the pre-digital age to the digital age,” Wagner said. “Michael recognized that digital technology self-organizes in the same manner as nature and biology and therefore he was able to effect meaningful change in both fields.”

A public celebration of life will be held Friday, May 27 at Broadway Studios, 435 Broadway, St., San Francisco. Doors open at 3 pm. with a service at 5 pm. A $20 donation is requested.

Survivors include his daughters Kate Gosney-Hoffman of Long Beach and Rachel Gosney of Las Vegas; mother Lou Gosney and brother Jeff Gosney, both of Greensboro, N.C.; sister Kimberly Bruton of Wilmington, N.C.; and three grandchildren.

Sam Whiting is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. Email: swhiting@sfchronicle.com